Episodes

Wednesday Apr 13, 2011

Waiting for Superman 2- Jim's Modest Proposal

Wednesday Apr 13, 2011

Wednesday Apr 13, 2011

Part 2

Education is in a bit of a crisis in this country. For years reformers have come and gone, each one promising an absolute solution to the problem. Sadly, few of them deliver. Let me be clear up front. I am not here to place blame on anyone. There are WAY too many factors that go into this mess to point at any one thing. More importantly, the why is largely irrelevant. Some people will scream and yell that "George Bush's 'No Child Left Behind' has RUINED education." Others will say, "Yeah, but Ted Kennedy wrote it, so it's HIS fault." For those who need that boogie man to point to, let me make the following statement to appease you.

"You are so right. I mean really. Can you believe how horrible and evil the people in the other political party are? Honestly! I am so glad that you are a member of the other political party, the one that would never do anything to screw anything up ever."

Does that make you feel better? Good.

What I am trying to get across is that it doesn't matter whose fault it is, we are in this situation and we have to do something about it.

Now that I have that out of the way, let's move on.

Given the fact that we live in the 21st century the odds are you have probably been on an airplane more than once. I've flown many, many times. Have you ever gotten onto a plane and said, "You know, I've flown many times. Hell, I've even watched 'Top Gun' and the 'Airport' movies a few times. What say we tell the captain that I'll be handling this flight."

This probably sounds very stupid to you. Just because you've flown and seen people fly doesn't mean that you have the technical expertise or the experience to pilot the thing. Well, believe it or not, I hear something very similar to this every day.

A quick story. At this year Austin Film Festival I was lucky enough to be in the audience for a panel featuring David Simon, creator of "The Wire," which is arguably the best show in the history of television. During the Q&A I seized the opportunity to ask a question that has been on my mind for the past 4 years.

In the 4th season of the show, a former police officer experiences his first year as a public school teacher after completing an alternative certification program. The season occurred, coincidentally, during my first year as a public school teacher after completing an alternative certification program.

"How did you get it right? How did you that experience so accurate?" I asked.

He responded, "That's all Ed Burns (his writing partner). He was a teacher in the Baltimore Public School System for several years. He didn't do alternative certification, but he taught. Actually, he said that teaching was the hardest job in the world. This is a guy who was a homicide detective for 20 years and did 2 tours as combat infantry in Vietnam. He said that teaching was the hardest job he'd ever had."

That hits the heart of it. You see, you could not do my job. Oh, you might think you can, but odds are that you can't. Unless, of course, you already do or already have done it, there is a very good chance that you couldn't do it. Most people go on about vacation time and things like that, to which I respond, "Yes, I do get more vacation time, but I also work with around 140 14 year olds every day. Want to trade?"

Nothing personal. It's hard. I know because, well, I teach. Specifically I teach 9th graders. There are several teachers I work with who look at me like I'm special forces. As I've said before many times, teaching 9th grade is like being left handed. Sure, you can work really hard and force yourself to do it, but you still aren't really left handed.

But aside from the grade level, teaching is a job that everyone thinks they can do, but really can't. Just because you've been on a plane and know where Dallas is on a map doesn't mean you can get the 747 there.

I know what you're wondering. How hard can it be? I know you're wondering this because it is the exact same question that went through my head when I set out on this path. How hard can it be?

Let me answer it with a story (By the way, if you are now or ever have been in my class, you're probably rolling your eyes at the phrase, "I have a story about that," and wondering why I write the same way I teach. If you haven't been in my class, I use stories from my life all the time to illustrate points. Kids remember more this way).

A few years ago a friends boyfriend made the following statement.

-I'm an engineer. I have a genius IQ. I could teach High School Science.

This amused me quite a bit, because a) I had heard such logic before, and b) he could not teach High School Science. So I asked a simple question.

-How?

-What?

- How would you teach it?

- Oh, I'd just go in and say, "Hey, I know this stuff, let's get to work."

I paused for a moment, wondering if I'd just stumbled onto a secret formula for teaching that had been overlooked for years. For a split second, my entire teaching career flashed before my eyes and I felt like a total failure! How could this be? How? Here I was spending all this time coming up with activities, finding ways to adjust curriculum, struggling with kids who just didn't get it. And this guy had just cracked the code. Then I came back to reality.

-Just go up there and tell them a bunch of stuff?

-Yeah.

-Well, what about the kids who don't get it? Or who don't care about the class and refuse to do work?

- What? Oh, they don't want to work they'll just fail.

- Just fail?

- That's right.

- So, you teach the kids who really want to learn physics or whatever, and fail the rest?

- That's right.

- And what do you do when the principal calls you into his office and asks why you have an 80% failure rate?

- What?

- 80% fail. What do you say?

- Well, I just say they didn't try and didn't want to be there.

- Ok, and then he'll say, "You don't get paid to teach the kids who really want to learn, you get paid to teach the kids who show up.

- But they don't try.

- So that means you don't have to? That might fly in college, but not here. What are you getting paid to do? A textbook could do what you're doing. Why aren't you teaching?

I swear that I saw a light go off in his eyes.

Let me illustrate a typical class for you.

This is a typical class of 30 students. 5 are way behind or don't care, 20 want to pass and do well even if some struggle with it, and the other 5 should/could be in an advanced placement course but just aren't. The first five will struggle, the last five will be bored out of their minds because of how far ahead they are from everyone else, and the middle 20 will be (hopefully) with you. There might be some variation from class to class, but this is a good guideline.

Every lesson you design has to hit and engage the 20 while being differentiated (that means tailored in some ways to students at different levels) enough not to lose the other 10.

Sadly, these numbers are me being generous. There are districts out there where the middle and top numbers are much lower. But that doesn't mean you are off the hook.

So, how do we fix things? Well, what we need to do is take a sharp critical look at how we do things and ask why we do them and see if there isn't a better way. I think there is. Right now I am working in a rather radical style that I find more effective and more effective than I could have ever imagined. We are changing the fundamental way we approach education and the results are amazing.

Let's start with some fundamentals before I discuss how to change them.

What are we teaching?

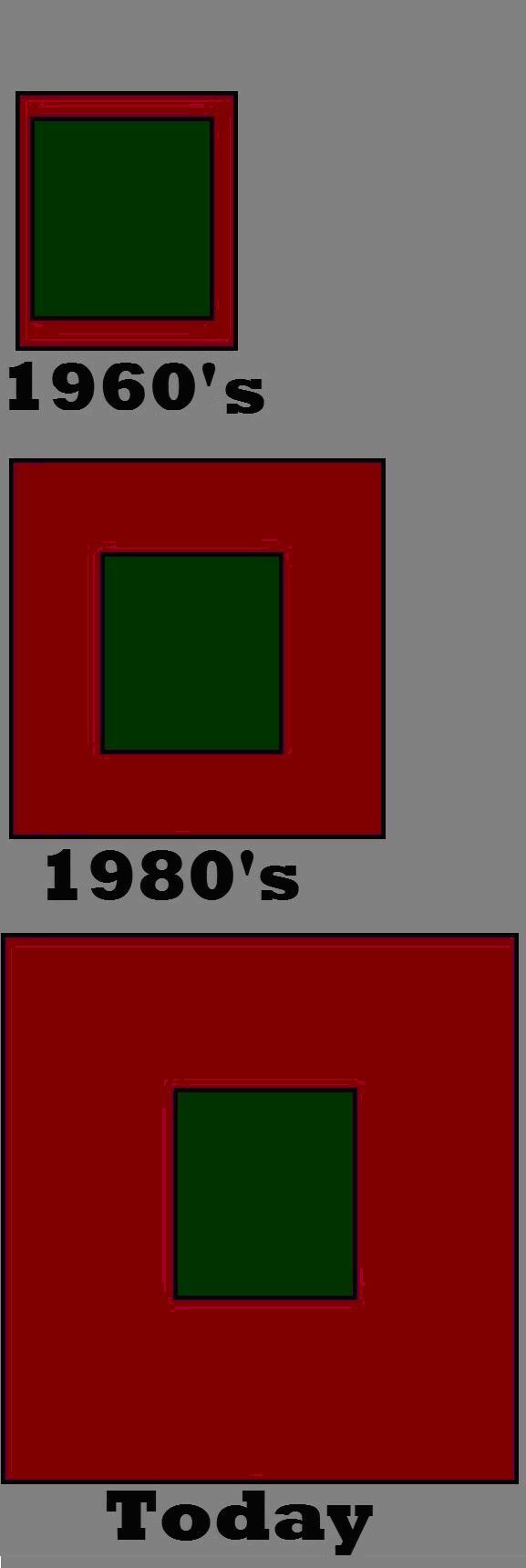

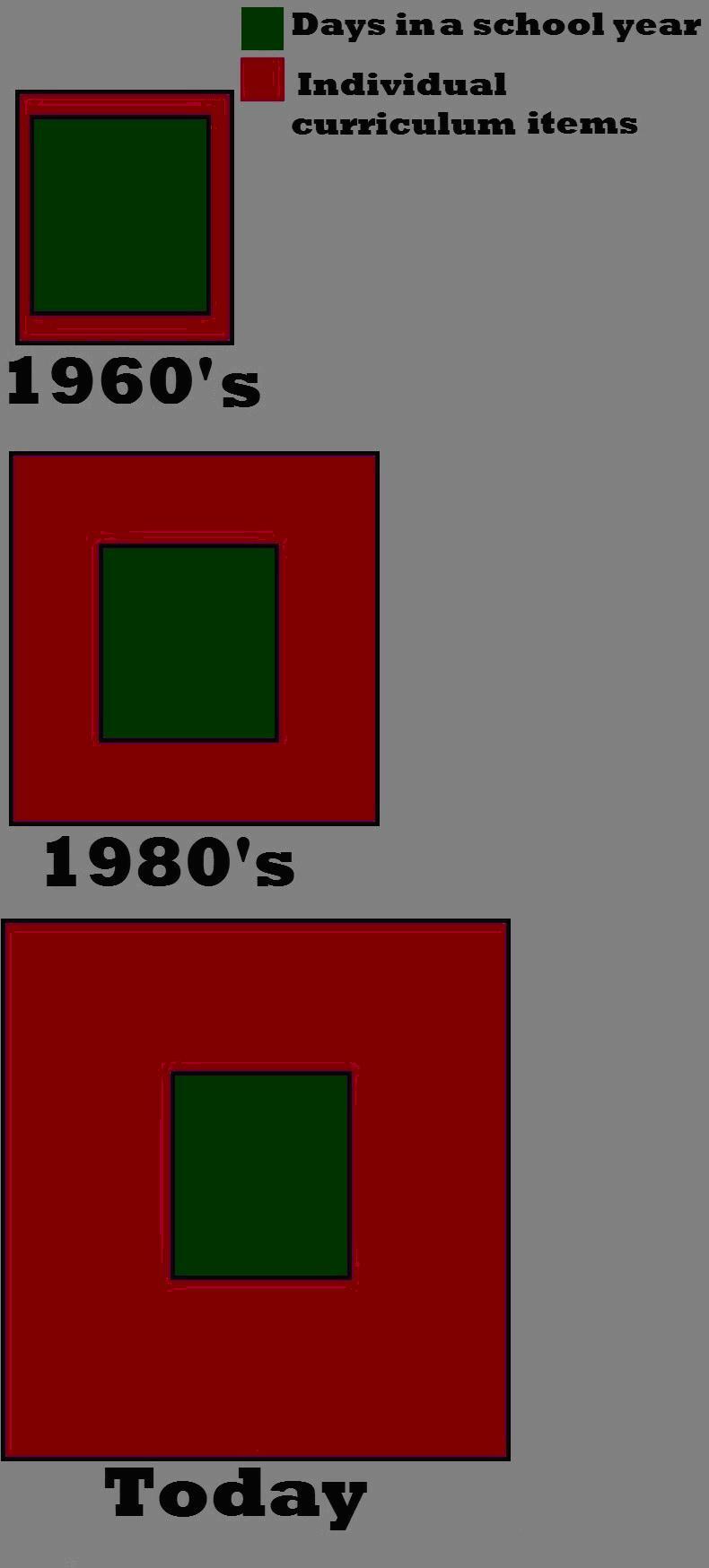

Here is a nice little graph that highlights what I see as the problem with education today.

So, that clears it up, right?

Oh, I forgot.

To be clear, the number of individual items on a course's curriculum has more than doubled while the school year has, in most cases, been shortened by a single day. This isn't a complaint about the amount of work there is to be done, but rather a comment on something that is patently ridiculous. An average high school course curriculum has 582 different objectives on it. Which means that you would have to cover several items every day without any chance to go back and review or re-teach any of them just to cover all the bases. Your students wouldn't learn any of it, but you would have covered it. The way most curriculum is written a student would have to go to school from K-22nd instead of K-12.

Current curriculum allows a social studies teacher about 1 week to cover imperialism, and includes 31 different terms and ideas that are to be taught. Is it possible to cover that volume of material and expect any of it to stick. Now take into account that kids are being asked to do this with 5-8 classes at one time.

Suppose we simplify this a little. Take a single class, let's use 9th grade English as an example, and ask a three simple questions.

1) What do I want students to know at the end of this class?

2) How will I know they know it?

3) What do I do if they don't?

If you were to take the three inch, not three ring but three INCH, binder of state standards and began to dig through it you could find a few dozen that you could individualize. So, let's break it down further. Each year consists, approximately, of six six week marking periods. So, I break out the six core ideas and ask those three questions.

Let's say I am working on a research unit. What do I want kids to be able to do? Well, I want them to be able to identify their position (write a thesis statement), identify sources to back up their claim (research and text evidence), support their claim (body paragraphs), summarize and restate their points (conclusion), and organize their ideas (rough/final draft).

What I just did was take the massive, overwhelming research section of that massive binder and reduced it to 5 items that are both TEACHABLE and MEASURABLE.

Now, there are things that aren't here that go into it, but this wouldn't be a first six weeks plan. You would have several marking periods to cover the information leading up to this (it's called scaffolding).

How is this revolutionary? Well, I would tell my students on the first day of the six weeks, "We are working on research this six weeks. I will be taking the following grades: intro and thesis, research and evidence, body paragraphs, conclusion, and rough/final draft. Those are the only grades I will be taking, but don't worry, you will have multiple chances to show me how well you can do each of these things."That last sentence, "multiple chances to show how well you can do each of these things," is the key.

Why are we so hell bent on only giving kids one chance to do something. Don't feed me that "real world" garbage. Does your boss only give you one chance to do something before firing you? Probably not. So, why should I only give one chance. You see, getting something wrong at first and then improving at it is called learning and the person who facilitates this learning is called a teacher. I'm not there to see what they already know, I'm there to teach them what they need to know.

Assignments and Grading

This brings me to the sticky subject of grading. So, I will ask a question, "What is the purpose of grading?" Most of you will say that we grade to see what a student knows. But I can prove you wrong right now.

Say you were teaching a class and you had a student who never did any of the homework. You give a test and he gets a 95 on it. But, you take grades on the homework and since he hasn't done any of it that pushes his grade down to a 60. Failing.

I'd ask why and you would say, "He didn't turn in the homework," and think that was that. But the real question is, "If he can get a 95 on the test without doing the homework, why should he do the homework?"

Normally homework is given to assist in understand the subject. But he is showing on the test that he understands it quite well. Yet you are failing him.

Why?

Simply put, his grade on subject mastery is an A, but his compliance grade is an F. So, the real question becomes, "Is your class about compliance, or mastery?" I understand the importance of turning in work, but if a student has the information down without doing an assignment, then that assignment becomes busy work and that grade becomes irrelevant.

But I will give an even better example.

I just pulled up an old grade book of mine, and by old I mean 3 years back, and was embarrassed by what I saw. For the six weeks that we read "To Kill A Mockingbird," I had the following grades entered:

Quiz Chapters 1-3

Quiz Chapters 4-8

Character Development Chart

Homework 1

Homework 2

Homework 3

Character paragraph

Seems pretty normal, right? So, why was I embarrassed? Look at the grades again and answer the following; what did my students learn that marking period?

You can't answer it, can you?

Now, suppose my grade book had, instead, looked like this:

Reading Strategy (main idea- theme)

Writing skill (summary)

Reading Skill (characterization)

Conventions of vocabulary (context clues)

Critical/Creative thinking (Character representing theme)

Can you tell me what a student learned this marking period? More to the point, if a student was failing, could I identify exactly what he or she needs to know to gain the skills they need?

You see, it's a lot easier to teach conventions of vocabulary (context clues), than it is to teach Homework 2.

So, why do we still give students grades based on compliance?

The thing is, once you start doing it, it really isn't that hard. My research grade book reads:

Identifying position (thesis statement)

Research

Supporting position (body paragraphs)

Summarize and restate points (conclusion)

Organize ideas (rough/final draft)

This way not only do I know what my students need to know, they know what they need to know, and they know that they can be wrong once and still be able to make it up.

How effective is this? Well, by using this strategy I was able to get a group of 9th graders (not Advanced Placement, just normal 9th graders) to pass an 11th grade, exit level standardized test (it was a released version that had been used by the state 4 years earlier) in one marking period. And it wasn't even difficult.

Why do we need to know degree of failure?

How much is an "A" worth? Really, how much? 100 points? 90? Truth is, it's worth about 10. That's right. There are only 10 ways to get an "A." For that matter, there are only 10 ways to get a "B," or a "C." But do you know how much an "F" is worth? It's actually worth 70 points. Don't agree? Look at this:

You might disagree with how I define "value" here, but I am doing it to prove a larger point. Why is an "F" worth so much? I mean, at a point it's clear that the kid doesn't get it, so why do we need to know that the kid "really, really" doesn't get it?

Here's how I think it should be done:

What this shows me is a level of understanding for the desired skill. Either they know it, or they are at some point of attaining it. This works better for two reasons. One, it removes degree of failure. Does it really matter if a kid got a 50 or a 20? Isn't the important thing that the kid didn't get it and needs additional support? Also, on objective assignments, things like essays and projects, can you honestly tell me that your grading system is so perfect, so flawless, that you can give me an absolute difference between an 89 and a 90?

However with this scale you can honestly say, " You didn't show a high level of mastery. There are some thing you didn't do, so we can go back and work on that."

Example:

You have two students in your class, their grades are as follows:

Student A-

85

85

90

0 (forgot a homework assignment)

80

Average- 68

Student B-

70

65

70

70

75

Average- 70

Now, based on grades alone, which student is more in need of tutoring? Student A is failing, so Student A must need more help. Is that true? No, he or she just forgot a single assignment. So, instead of focusing attention where it is needed, we are diverted because of one missing assignment.

Let's try this the other way.

Student A-

3

3

4

M

3

Average- 2.6 (between basic and proficient)

Student B-

2

1

2

2

2

Average- 1.8 (between basic and below basic)

Which of those students is more in need of help? Now it's clear that Student A, though missing an assignment, has a basic grasp on the information and Student B is struggling. Now it's easy to identify the areas of need and help the kid learn. That's the difference. In essence, the 100 point scale is about grading, the four point scale is about learning, and I we need to get out of the business of grading and into the business of learning.

So, what does it all mean?

Let me be clear up front; I am not proposing this as a magic fix it for every school. As I’ve said before, there is no such thing as a simple solution to so complex a problem as public education. There are way too many factors that come into play to pretend, even for a moment, that there is a single, one size fits all solution.

All that I am presenting her is something that I have seen immense amounts of research proving its efficacy, and have personal experience that backs that research up. It doesn’t just help high achieving kids achieve more (but it does do that), it doesn’t just help the kids in the middle reach higher levels (which it also does), it also helps the kids who would typically struggle just to pass actually learn the information and move from Cs and Ds to Bs and As.

While it isn’t a fix all, it is something that the film “Waiting for Superman” doesn’t present. It is an approach to teaching and learning that can be brought to scale and used widely without all the difficulty of opening a charter school.

We have to deal with most of this because of standardized tests. Let me say two things. First, standardized test are garbage and have nothing whatsoever to do with actual academic achievement. Second, they aren't going anywhere. Not only aren't they going anywhere, but now the federal government is giving out funding that requires new tests to be adopted. Now you can fix your schools budget problems by adding a test that will take time away from learning to see if your child can pass a test that doesn't really show anything other than the fact that they can pass a test.

As hard as it seems, we need to stop thinking of education as a “well, this worked when I was a kid, so it’s fine now” situation. The way we did things in the past is no longer good enough. It just isn’t. We are working to educate children to do jobs that don’t exist yet in a world that will look significantly different than it looks today. We need to teach adaptability and concrete understanding, not just compliance.

But more than that, we have to admit that the world our kids are growing up in is vastly different than the one we had. We didn’t grow up with unlimited access to the adult world. We didn’t have a culture built on ignorance, violence, and short term gain. We didn’t grow up in a time when your average FRESHMAN classroom has at least one parent in a student desk. We have created (and yes, WE created it, THEY didn’t) a world that is increasingly hard on young folks and that has to be respected.

Those problems I cannot offer a solution for. What I can do is promise that as long as I am able I will be in my classroom doing everything I can to help.

No comments yet. Be the first to say something!